European Memories

of the Gulag

BioGraphy

Anatoly SMILINGIS

Anatoly Smilingis was born on 4 October 1927 in Plungė, Lithuania. His mother was a teacher and his father a headmaster and head of a local nationalist party. The family was deported on 14 June 1941. His father was then separated from the rest of the family. Forever.

At the age of 14, Anatoly was left with his mother and little sister Rita. After a long journey by train and river barge, they arrived in the Komi Republic. In the special settlement village “Второй участок (second section)”, his mother found an indoor job in the public baths, while Anatoly worked in the forest as a tree marker. At the start they still had food supplies, but by the winter of 1942 things rapidly got worse and famine was widespread. After his mother was arrested and sent to a camp for stealing a few oat grains, Anatoly began to swell up from hunger and nearly died.

Barely had he recovered than he went back to work in the forest. After the war, he got a job at the Negakeros forestry enterprise. He so loved the forest that in the early 1950s he began running excursions for children.

In 1955, Anatoly received an official letter from Lithuania announcing his release. But he never left his land of exile. His hiking trips with children had brought him a reputation as a sportsman and social recognition. Anatoly now supports memory work and memory tourism, which he has pioneered in this region.

The interview with Anatoly Smilingis was conducted in 2012 by Hélène Mondon.

-

Excitement at leaving

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseExcitement at leaving

Anatoly was 14 when he heard he and his family were being deported to somewhere in Siberia. His memories of the episode make him smile as he tells the story in these two extracts. The boy he was then did not see this departure as a tragic deportation but rather as an exciting long trip that aroused his curiosity.

-

Excitement at leaving - Preparations

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseExcitement at leaving - Preparations

When two soldiers burst into their house to tell them to get ready, Anatoly, keen on chemistry, quickly filled his pockets with all sorts of chemicals. With a laugh he recalls the reaction between the glycerine and potassium permanganate that set fire to his trousers, and startled the officer who had come to execute the search warrant.

-

Deportation folklore

Deportation folklore

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseDeportation folklore

During the journey, the mothers sang songs from Lithuanian folklore. They also composed lamentations to express their suffering and desire to return home. Anatoly shyly sings a verse he remembers.

-

Facing death - The death of the “Persians”

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseFacing death - The death of the “Persians”

At “Second section” village, there was such a mixture of people that Lithuanians, Poles, Chinese, Iranians and Germans got along well together. The Iranians, who the Lithuanian women romantically called “Persians”, came from the upper classes and stood out for their elegance and outspokenness. But they could not, or would not, adapt to the harsh conditions of exile. Anatoly tells the tragic story of their death, adding that it haunted his nights long afterwards:

One December morning, four “Caucasian Persians”, skinny and ragged, were sent out to work in the forest. They were given tools. Anatoly’s job was to lead them to the worksite and come back later and count how much timber had been cut. They trudged about one kilometre in the icy cold, and the Persians found it hard to keep up. At the worksite, Anatoly explained to them what they had to do in a mixture of Russian, Chinese and Lithuanian. The Persians were only interested in one thing: keeping warm. So Anatoly made a fire and left them a few logs. At nightfall Anatoly came back for them, but, seeing no smoke, began to get worried. He thought they might have run off. When he got to the place, he found them sitting frozen stiff. They had all died of cold.

In exile, death was a daily occurrence and you had to learn to cope with it, whatever the season. Several times Anatoly had to transport bodies in the depths of winter for the exhausting ritual of burial. He describes one of these “operations”: the corpses were drawn by horses to the cemetery in Postkeros. This happened twice a day. In the cemetery, the snow had to be cleared, then holes dug with axes, hard work in permafrost conditions. He would dig, then cover the corpses with snow. The complications came with the spring, when the snow thawed. Starving stray dogs came and ate at the bodies, before the Chinese came hunting the dogs, which they ate. So farm workers from the kolkhoz were called to help bury a second time the corpses gnawed at by the dogs.

-

Facing death - The ritual of burial

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseFacing death - The ritual of burial

At “Second section” village, there was such a mixture of people that Lithuanians, Poles, Chinese, Iranians and Germans got along well together. The Iranians, who the Lithuanian women romantically called “Persians”, came from the upper classes and stood out for their elegance and outspokenness. But they could not, or would not, adapt to the harsh conditions of exile. Anatoly tells the tragic story of their death, adding that it haunted his nights long afterwards:

One December morning, four “Caucasian Persians”, skinny and ragged, were sent out to work in the forest. They were given tools. Anatoly’s job was to lead them to the worksite and come back later and count how much timber had been cut. They trudged about one kilometre in the icy cold, and the Persians found it hard to keep up. At the worksite, Anatoly explained to them what they had to do in a mixture of Russian, Chinese and Lithuanian. The Persians were only interested in one thing: keeping warm. So Anatoly made a fire and left them a few logs. At nightfall Anatoly came back for them, but, seeing no smoke, began to get worried. He thought they might have run off. When he got to the place, he found them sitting frozen stiff. They had all died of cold.

In exile, death was a daily occurrence and you had to learn to cope with it, whatever the season. Several times Anatoly had to transport bodies in the depths of winter for the exhausting ritual of burial. He describes one of these “operations”: the corpses were drawn by horses to the cemetery in Postkeros. This happened twice a day. In the cemetery, the snow had to be cleared, then holes dug with axes, hard work in permafrost conditions. He would dig, then cover the corpses with snow. The complications came with the spring, when the snow thawed. Starving stray dogs came and ate at the bodies, before the Chinese came hunting the dogs, which they ate. So farm workers from the kolkhoz were called to help bury a second time the corpses gnawed at by the dogs. -

Pangs of hunger - His mother’s arrest

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

ClosePangs of hunger - His mother’s arrest

During the first months of their deportation, Anatoly’s family survived on supplies imported from Lithuania. But in the winter of 1942 things got worse and anything went when it came to keeping the family alive.

“My little sister Rita was looked after in the boarding house at school, where the youngest children had board and lodging. We had to eat too, so Mother started going to the stables more often. Occasionally the horses were fed a few grains of oats. She began to bring some home, I wondered where from, she ground them into flour and cooked it. It cost her dear. Someone saw her and she was arrested for a handful of oats. I never saw her again. They took her away and she died somewhere in a camp. I was on my own.”

Anatoly began life as an orphan and had the terrible experience of famine, which he says he really suffered from for nearly six months. In this sequence he tries to explain what a child felt during the final stages of hunger:

“We had nothing left to eat. I remember some episodes. Somehow or other I had managed to barter something for a loaf of black bread, a whole loaf! I ate it and it was as if it was nothing. I ate it and yet it didn’t feel like it. I cut it up into tiny pieces on the stove and suddenly there was none left. And then, you can cry your eyes out, it’s all over, all gone. I can still remember. And I started swelling up, it started in my legs. It was well known: some who started swelling hadn’t long to go, then your stomach swells. And you know, you become completely indifferent to everything, you turn into a zombie. But I was still hungry, except that I had legs like lead and I could barely lift them. I can still remember.”

-

Pangs of hunger - Famine

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by H. Mondon, 24/08/2012.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

ClosePangs of hunger - Famine

During the first months of their deportation, Anatoly’s family survived on supplies imported from Lithuania. But in the winter of 1942 things got worse and anything went when it came to keeping the family alive.

“My little sister Rita was looked after in the boarding house at school, where the youngest children had board and lodging. We had to eat too, so Mother started going to the stables more often. Occasionally the horses were fed a few grains of oats. She began to bring some home, I wondered where from, she ground them into flour and cooked it. It cost her dear. Someone saw her and she was arrested for a handful of oats. I never saw her again. They took her away and she died somewhere in a camp. I was on my own.”

Anatoly began life as an orphan and had the terrible experience of famine, which he says he really suffered from for nearly six months. In this sequence he tries to explain what a child felt during the final stages of hunger:

“We had nothing left to eat. I remember some episodes. Somehow or other I had managed to barter something for a loaf of black bread, a whole loaf! I ate it and it was as if it was nothing. I ate it and yet it didn’t feel like it. I cut it up into tiny pieces on the stove and suddenly there was none left. And then, you can cry your eyes out, it’s all over, all gone. I can still remember. And I started swelling up, it started in my legs. It was well known: some who started swelling hadn’t long to go, then your stomach swells. And you know, you become completely indifferent to everything, you turn into a zombie. But I was still hungry, except that I had legs like lead and I could barely lift them. I can still remember.” -

Exile with no return

Exile with no return

The Smilingis family. His parents, Anatoly and his sister Rita. Plungė, Lithuania (Photograph, Anonymous, 1939). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

The Smilingis family. His parents, Anatoly and his sister Rita. Plungė, Lithuania (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

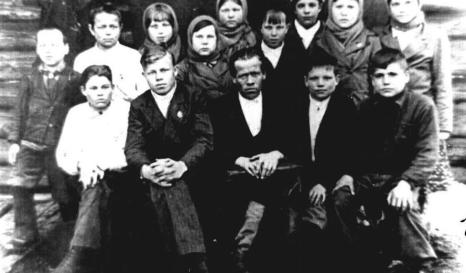

Children of special settlers, Kortkeros orphanhood (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940-1950). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Plank road (лежнёвкa) to Sobino (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940-1950). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Timber rafting (Photograph, Anonymous, 1959). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Timber rafting (Photograph, Anonymous, 1959). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anatoly Smilingis with a tame bird of prey (Photograph, Anonymous, 1952). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anatoly Smilingis on expedition (Photograph, Anonymous, 1960). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Young people from the Belka tourism club run by Smilingis (Photograph, Anonymous, 1970-1980). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Commemorative plaque on a cross erected by former deportees, cemetery of special settler village “Second section”, Kortkeros (Photograph, Anonymous, 2009). Source: Anatolij Smilingis's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseExile with no return

Anatoly could go and live in Lithuania; he has not only a passport but also a flat he was given as compensation for his treatment. But something keeps him in Kortkeros: his wife, no doubt, and also his love of the forest, which he knows by heart after hiking across it with the boys of the Belka sports club. Anatoly says he feels useful here, he is integrated and wants to continue his research into the history of the purges and the remains of mass burial sites in the region.