European Memories

of the Gulag

BioGraphy

Anna KOVALCHUK-TARASOVA

Anna Kovalchuk was born in western Ukraine, then in Poland, in 1937. She spent the war there. When it ended, she was deported with her mother and brothers (including Grigori) to the Arkhangelsk region, after they were denounced by a neighbour for being followers of Bandera, although her father had been shot by the banderovci for being pro-Soviet.

After two years in exile, her mother decided to escape with her children and return to her village. She bartered her shawl for a train ticket and set off on the long journey, via Moscow, where she took a lorry from one station to the other, and Kyiv. Many people on the trains helped her.

Some time later in their village, they were denounced again by a neighbour and deported to the same place. Then they were taken by train to Siberia, to Bratsk, at that time a small village, and then to a village of Ukrainians near Kaltuk. She married a farmer in Kaltuk and settled there and worked on the farm.

In 1984, she had health problems and the couple moved to Ukraine, near Chernobyl. After the nuclear power station disaster, they moved to Irkutsk, where they had more difficulties settling in.

The interview with Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova was conducted in 2009 by Emilia Koustova and Larissa Salakhova.

-

Extermination of Jews and other violence

Extermination of Jews and other violence

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseExtermination of Jews and other violence

Audio available / -

Violence: rape during the war

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseViolence: rape during the war

Audio available /“We built her [Anna’s aunt] a house, a little brick house with two rooms. And then, again, one of the Bandera men came, when that German was dead. He came and made her pregnant; a man from her own village came and raped her.

He said, open up, she opened, what could she do, what sort of door did she have in her house? And that was it. That’s what life was like then. There was no authority. The master, the one in a position of authority, could have all the women he wanted. Of course, they raped.

But there were some good ones too.

{Anna’s husband speaks:} Yes, that German who gave Anna chocolate;

{Anna again:} he used to cuddle me and give me sweets. But I realised that he had children at home. He showed me the photos. In four years I learnt to speak German well. I heard German around me every day and I had a good memory.

There were some decent Germans who spoke to us, not all of them. All the children began speaking German. We were used to hearing German.”

-

Arrest: the neighbour

Arrest: the neighbour

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseArrest: the neighbour

Audio available / -

Arrest and deportation

Arrest and deportation

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseArrest and deportation

Audio available /“We didn’t live long like that. They came for us, ‘Get ready to go’ and off we went. The children were put on a cart, a whole cartload of children, and they drove us off. They drove us off worse than dogs. In those wagons, the goods wagons, all on top of each other, there were sorts of bed frames, planks, that’s how we slept, all day we were sitting and lying, and the journey went on a very long time. Where to? Up in the north, the Arkhangelsk region, later they called part of it the Vologda region, but it’s all the same. We were taken a long, long way. We suffered, there were no lavatories, we held ourselves, men and women, children and old people, worse than dogs, starving and freezing, and finally we got to the village of Privodino on a bend in the Northern Dvina.”

-

Escape

Escape

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseEscape

Audio available /“I was bringing water back to the house. Mother said, ‘We’ll die if this goes on! Come on, let’s go to Ukraine.’ She didn’t ask what we thought. We were young then; she took someone’s sleigh and off we went. She put us in the sleigh and wrapped us up. She wrapped up my elder brother, the one who’s in St Petersburg now; she tore up a dress and wrapped him in it.

It was freezing, and we got to the Yadrikha railway station, and she put us on the train. On the train some people felt sorry for us and gave us a bit of food, and when we arrived, everyone could see that Mother was bloated with hunger and so were we. We were frozen, everything was frozen, my hands, my feet, and that’s why they still hurt even now.

[…]

We had nothing, nothing at all. Then Mother said, ‘We’ll die like this; let’s go back to Ukraine.’ [Question] Mother had a silk shawl and she gave it to the woman working at the station in exchange for a ticket. There are some nice people — there are some — you can’t say that everyone is bad. People gave us food. They realised we were escaping, Mother told them, and anyway it was obvious; we were in a normal train with normal carriages. We went via Moscow, we crossed Moscow in a lorry from one station to another, because the ticket covered the whole journey and that’s how we came home.”

-

Denunciation for theft and serious consequences

Denunciation for theft and serious consequences

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseDenunciation for theft and serious consequences

Audio available / -

Childhood in exile

Childhood in exile

La mère et la tante d'Anna Kovalchuk autour de sa grand-mère (Photograph, Anonymous, 1930-1940). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

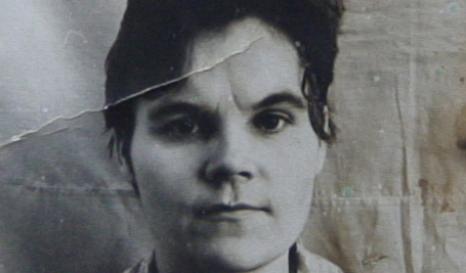

Anna Kovalchuk’s mother and aunt with her grandmother (Photograph, Anonymous, 1930-1940). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

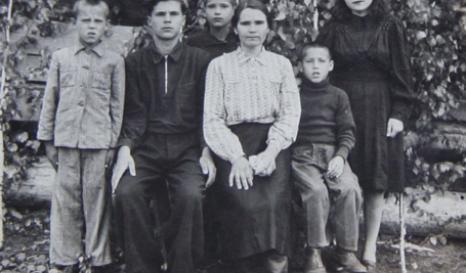

Just after arriving at the place of deportation in Bulak, Irkutsk region, Anna Kovalchuk’s mother with all her children (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1948). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

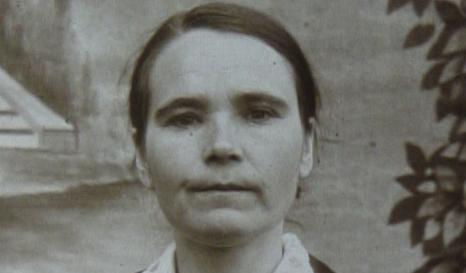

Anna Kovalchuk’s mother in exile (Photograph, Anonymous, 1946-1952). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk and 4 deported Ukrainian friends in Bulak (Photograph, Anonymous, 1952-1953). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk in Bulak, Irkutsk region (Photograph, Anonymous, 1954). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Grigori, Anna Kovalchuk’s brother, in Bulak, Irkutsk region (Photograph, Anonymous, 1946-1952). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk as a student in Novosibirsk (Photograph, Anonymous, 1954). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk (top right) with three students in Novosibirsk (Photograph, Anonymous, 1954). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk and a student friend in Novosibirsk (Photograph, Anonymous, 1954). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk just after her marriage (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk just after her marriage (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk’s husband just after their marriage (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk and her husband at the time of their wedding (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk and her husband at the time of their wedding (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Anna Kovalchuk’s mother and her grandchildren after their return to Ukraine (Photograph, Anonymous, 1948). Source: Anna Kovalchuk-Tarasova's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseChildhood in exile

These photographs were taken at the start of the deportation period, then after liberation. One early photograph, with Anna’s mother and grandmother, dates from before deportation.

Many details reveal the nature of life in exile, particularly on one photograph taken just after their arrival: the mother poses with her children, who are still wearing odd shoes, showing their extreme poverty. Anna recalls that her brothers went to school every other day in turn, because they only had one pair of shoes between them.

-

Children’s work — nurse

Children’s work — nurse

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseChildren’s work — nurse

Audio available / -

Daily life — delivering frozen milk

Daily life — delivering frozen milk

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseDaily life — delivering frozen milk

Audio available / -

Death of Stalin and liberation

Death of Stalin and liberation

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseDeath of Stalin and liberation

Audio available /