BioGraphy

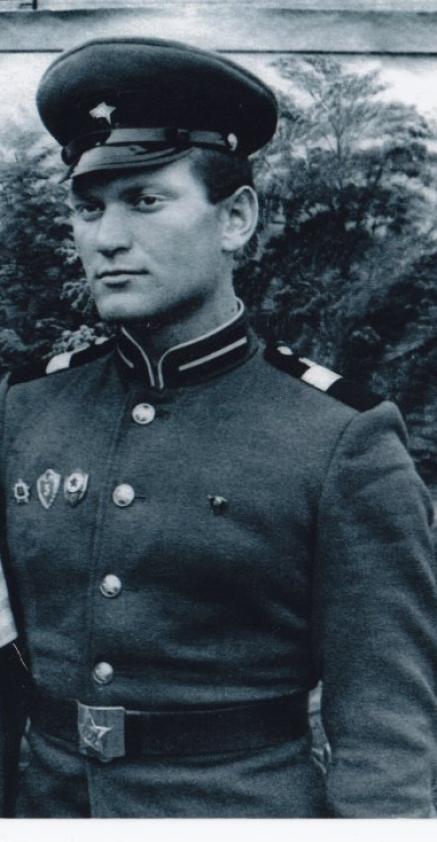

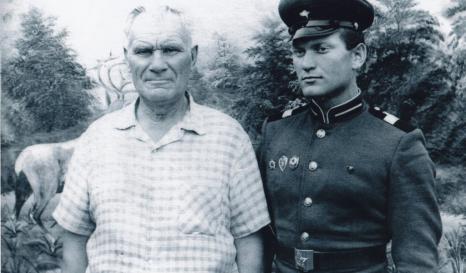

Jonas MAŠALAS

Jonas Mašalas was born in 1947 into a large family consisting of six children and his parents. They were deported from their home village Šakarniai on March 29, 1949, when Ionas was only one and a half years old. In the 1930s, his father had traveled to Buenos Aires, where he had acquired skills as a brewer and had built up a nest egg to start a brewery upon his return to Lithuania.

According to the information circulating in the family, the family was deported following a denunciation of a relative, his father's brother Dzidoris, at the time a fighter (iastrebok) and leader of the local komsomol cell. This internal family conflict intersects with the economic reasons for their deportation: Dzidoris had founded a family and married a woman from a poor family, against the wishes of his brother, Jonas' father.

Deported to the Irkutsk region, Ionas' parents worked in a kolkhoz. They shared a house with other displaced persons, then gradually stabilized their income and built their own home. 11 Lithuanian families lived in this special village. They maintained close ties of mutual aid and sociability. Lithuanian holidays and religious holidays were celebrated as well as November 7. The skills of the deportees were highly valued by the local inhabitants. While working, the children continued their studies and Ionas was particularly encouraged to do so by his older sister. At the age of 7, he started to attend the village school Abramovka. In 1965, he graduated from high school.

Having worked as a tractor driver, he completed his military service and attended the Higher Officers' Course. Three times he tried to enter the Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but his application was systematically rejected when his file had to be stamped by the KGB. "Your file must be marked 'son of a kulak'. That's it," one of his officer friends explained to him. Ionas then joined the police. In 1971, he entered the Faculty of Law at the University. Afterwards, he taught at the police academy for 11 years, and also headed a kommandantur. In 1992 he became a colonel and from then on his career did not seem to be hindered by his deportation background. In 1996 and 1997, as head of the OMON (Special Purpose Mobile Detachment), he went to Chechnya.

The Mašalas family remained in the special village, while in the early 1960s, being liberated, all other Lithuanian households left it. Jonas' father and his elder sister traveled to Lithuania and decided not to change their living conditions and to stay in Siberia. Painfully for the family, Dziduris, the father's older brother, lived in the Mašalas' house.

In 1974, Jonas Mašalas tried to continue his career as a policeman in Vilnius. The interview he had with a local officer, who, according to his observations, might have been involved in the deportations, convinced him to stay in Siberia. Ionas's path was formed at the intersection of an attachment to the Lithuanian language and culture and an aspiration (rare among deportees) to become a party member and a soldier.

Interviews with Jonas Mašalas were conducted in 2013 and 2014 by Emilia Koustova and Alain Blum.