BioGraphy

Irena AŠMONTAITĖ - GIEDRIENĖ

Irena Ašmontaitė-Giedrienė was born in Šiauliai, Lithuania, in 1935. Her father was a mechanic and her mother a telegraphist. In 1941, the family was arrested and the father separated from them and imprisoned. Her pregnant mother and the three children were deported first to the Altai region (where their little brother was born) and a year later to the Far North of Siberia, to Trofimovsk near the Laptev Sea in the Arctic Ocean. There, their mother fell ill and the three children were placed in an orphanage. Irena lost nearly all her family in these freezing, inhospitable places: first her little brother, born in the Altai, a few days later her mother and a month after than her sister.

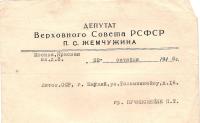

Then she was moved to an orphanage in Bulun, in the Yakutsk region. Her grandmother wrote to Polina Zhemchuzhina, Molotov’s wife, to be allowed to bring her back to Lithuania. The first attempt failed because the person who was supposed to look after the trip took the money and disappeared, leaving the girl at Yakutsk airport. Finally, in 1946, Irena managed to return to Lithuania with other orphans. She moved in with her grandmother in her native town where she went to school and became a nurse.

The interview with Irena Ašmontaitė-Giedrienė was conducted in 2009 by Jurgita Mačiulytė.