BioGraphy

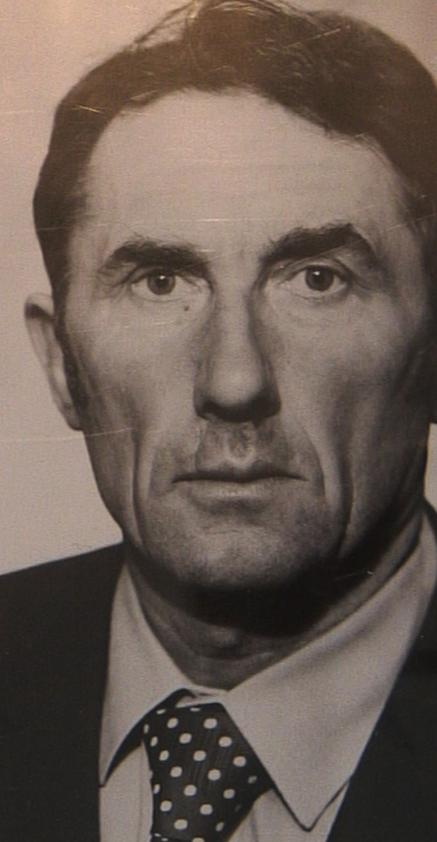

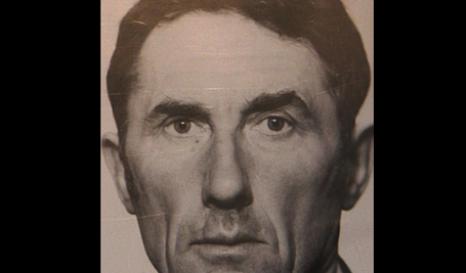

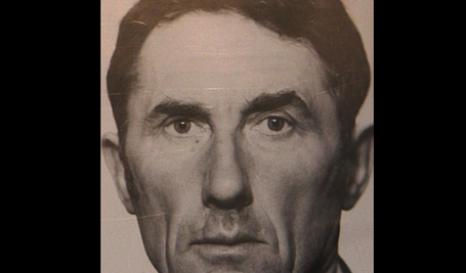

Juozas MILIAUSKAS

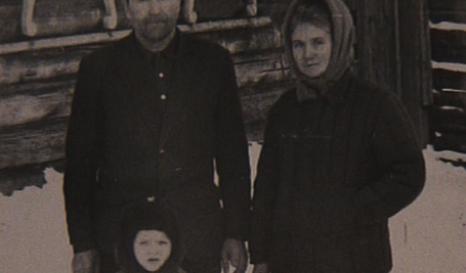

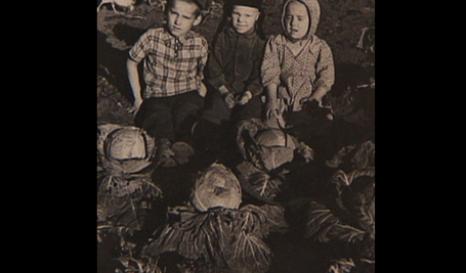

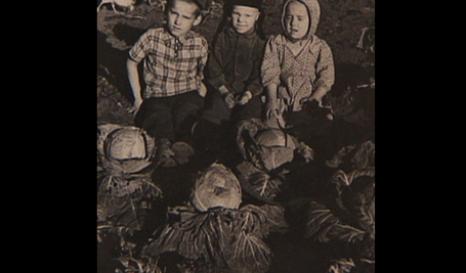

Juozas Miliauskas was born near Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1934. He lived in the country with his parents, his father, a workman, and his mother, a housewife.

After 1947, the family feared arrest. One of his father’s brothers had joined the “Brothers of the Forest”. Several times they hid with friends or neighbours, in 1947 and 1948. But on 17 March 1949, four NKVD soldiers, speaking Lithuanian among themselves, came for them. They were taken to the station in a cart and then locked in a goods wagon. They had only half a sack of flour with them.

The train went to the Irkutsk region. From there they were taken by lorry and then sleigh to the village of Chichek in the back of beyond. There they worked the land and were paid by the collective farm in trudodni (labour days). His parents reported to the commandant once a month. Their neighbours helped them out with a few potatoes or other useful things. They spoke Lithuanian among themselves but Juozas learnt Russian from the local young people.

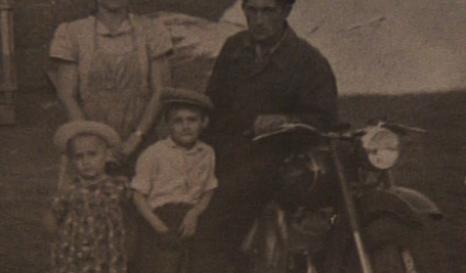

He became a tractor mechanic, then a driver, a step up that made his life more comfortable.

In 1956, he was released from his status as a “special resettler” and in 1957 he returned to Lithuania with his parents. But by now he was a Siberian. “There was nowhere to live”, “We didn’t belong”. Six months later he decided to go back where he came from, Siberia, took up agricultural work again and then moved to Bratsk, a village that had become an industrial city. He still lives there today.

The interview with Juozas Miliauskas was conducted in 2009 by Emilia Koustova and Larissa Salakhova.