BioGraphy

Sonia BORY

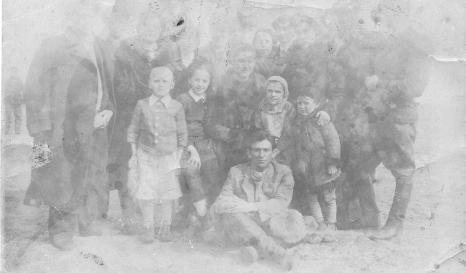

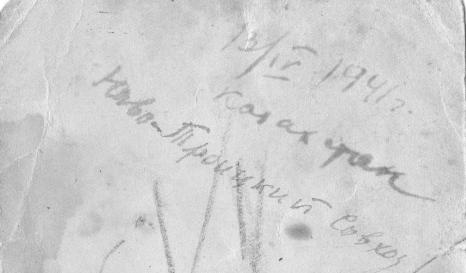

Sonia Bory was born in Wołożyn, Poland (now Valozhyn, Belarus), to a well-known Polish rabbinical family. A few months after the Red Army arrived in Wołożyn, her father, co-owner of a sawmill and a flour mill, was arrested and sent away to a camp in the Gulag. Shortly after his arrest, Sonia Bory was herself deported, along with her mother and brother, to a sovkhoz in northern Kazakhstan.

Sonia Bory, her mother and brother, lived in exile in the USSR for six years. Sonia's mother worked as a bursar in the sovkhoz dispensary. After serving in an NKVD labour column, her brother became a non-commissioned officer in the Red Army following the Sikorski-Maisky agreement between Poland and the USSR in 1941.

After being interrogated by an NKVD agent, Sonia's mother left the sovkhoz in secret for Pavlodar, in north-eastern Kazakhstan. Sonia and her mother were not sent back to Poland until 1946, to Szczecin, a German town that had become Polish. They learned of the death of relatives and family members who had remained in Poland and been exterminated during the Nazi occupation, but had no information about Sonia's father, who they thought was dead. After a few months in Szczecin, they crossed the border illegally into Germany and then obtained a visa for France to join part of their family who had survived the war. Sonia's brother deserted and fled to Germany, then to France with a Jewish Zionist organization, before settling permanently in Israel.

In Paris, Sonia Bory enrolled in higher education and then pursued a career as a chemist.

The interview with Sonia Bory was conducted in 2012 by Marta Craveri and Alain Blum.