BioGraphy

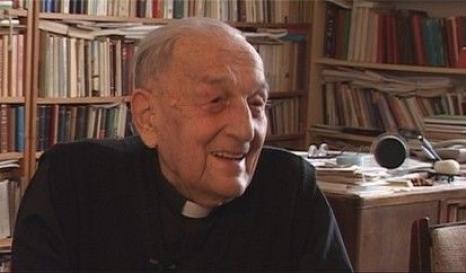

Placid KAROLY OLOFSSON

Father Placid Károly Olofsson was born in Rákosszentmihály, Hungary, in December 1916 to a father who taught at secondary school and painted in his spare time and a mother of German origin. He grew up in an intellectual, very Christian environment and in 1933, after Benedictine secondary school, he studied theology and German language and civilisation. He gained a doctorate and was ordained a priest.

During the war, he was a padre in a military hospital, then taught in a Catholic secondary school in the provinces and then in Budapest. In January 1946, the Hungarian political police arrested him. He was sentenced to 10 years’ forced labour because his participation during the free elections in 1945 in the electoral campaign for the Smallholders Party was considered an offence. He was first held in a Budapest prison guarded by Soviet soldiers. As he worked cleaning the corridors, he administered Extreme Unction to those condemned to death by singing it in Hungarian so the guards could not understand.

Throughout his imprisonment he set himself the task of “awakening the minds” of his fellow prisoners, comforting them, so that they might “feel the presence of God” and feel human. In his view, it was not the Red Army that sent him to the Gulag but the will of God to submit him to that trial. “God has a great deal of humour and a sense of irony”, he said later. During all the years in the Gulag, using every trick in the book, he always did his “duty”: celebrating Mass at night in the huts with grape juice and unleavened bread, and running “competitions for treats” so that “his companions could escape their surroundings”. He worked sawing timber and then in the furniture workshop. One day, he became the camp painter and did portraits of guards and common law prisoners. He was released in 1955 and returned to Budapest, where he was not allowed to practise as a priest. He found work at a locksmith’s, where he lost a finger. After being accused of sabotage, he ended up as a labourer in a hospital laundry, finally becoming its director, while still leading underground prayer groups.

After his retirement in 1977, he gradually took up with the Church again and now practices still as a priest.

The interview with Placid Karoly Olofsson was conducted in 2009 by Anne-Marie Losonczy and David Karas.