European Memories

of the Gulag

BioGraphy

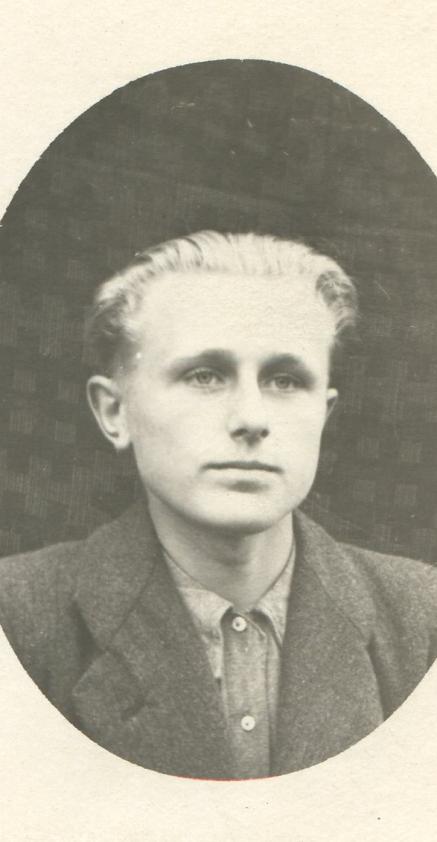

Rimgaudas RUZGYS

Rimgaudas Ruzgys was born in the small town of Tryškiai in northern Lithuania in 1937. His parents were well-to-do farmers and owned 35 hectares of land. In May 1948 the Soviet authorities prepared the deportation of the farmers to speed up collectivisation and stop the support they were giving the armed resistance. So the Ruzgys family were arrested and deported to Buryatia.

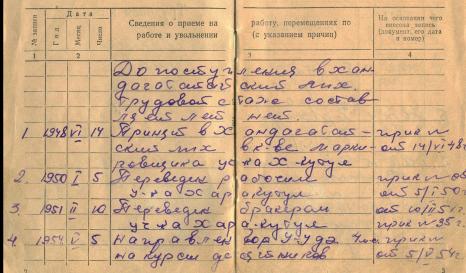

After attending school for a year in Siberia, Rimgaudas, barely 11 years old, began work at a lumber camp, a highly dangerous, exhausting job. Not until 1960, after three and a half years’ military service, did Rimgaudas return to Vilnius. Settling back in was not easy: “No one wanted to give me any papers in Lithuania. They said, ‘Go back where you came from’.” Thanks to an acquaintance, he managed to establish residence in Lithuania and began working as a bus driver.

He took up his education again, first at evening classes, then a vocational school and finally a higher education institution. For twelve years he studied every evening and worked during the day: “There were days when I didn’t have time to sleep.” However, he got his qualifications and began a career as transport manager for a trade union. Now, although he is retired, Rimgaudas keeps busy. He’s been working for nearly sixty years.

The interview with Rimgaudas Ruzgys was conducted in 2009 by Jurgita Mačiulytė.

-

Before and during deportation

Before and during deportation

Rimgaudas Ruzgys's maternal grand-parents and parents before deportation (Photograph, Anonymous, 1930). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A happy childhood: playing in his native countryside (before deportation) (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940-1947). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A happy childhood: playing in his native countryside (before deportation) (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940-1947). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas’s mother (right) with her sister before deportation (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1930). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys (right) and his brother in front of the house where they were born, before deportatio (Photograph, Anonymous, 1945-1947). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

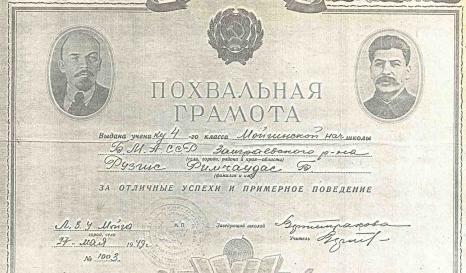

Rimgaudas Ruzgys’s Class 4 (Year 4) certificate, his only year of schooling in deportation (Photograph, Anonymous, 1949). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Employment record book, showing that he started work at the age of 11 (Photograph, Anonymous, 1948). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys takes a break at work in Buryatia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953-1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys playing the accordion in deportation (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953-1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

The Ruzgys family in Novoilyinsk, their last residence in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1958). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseBefore and during deportation

-

Preparing for the journey

Preparing for the journey

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

ClosePreparing for the journey

“At that point, the parents began making lots of preparations. They got rid of all they could, all their best property. For example, they gave their bees and best furniture to their neighbours. They began to collect money and food. Mother began to bake bread, dry it and put it in bags. She tied labels on the children with their first and last names so they could be found if they got lost. She sewed a gold coin into each child’s clothes so they could use it to live on, if anything happened to them.”

-

Travels of the Ruzgys family

Travels of the Ruzgys family

The Ruzgys family in Siberia. Rimgaudas, first from right (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

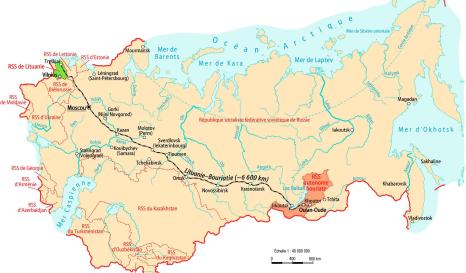

Leaving Lithuania (spatial trajectory map of the Ruzgys family) (Map, Mindaugas Baltrušaitis, 2012). Source: Sound Archives. European Memories of the Gulag.

Media subject to copyright.

From Lithuania to Buryatia – the journey in 1948 (Map, Mindaugas Baltrušaitis, 2012). Source: Sound Archives. European Memories of the Gulag.

Media subject to copyright.

Map of the Ruzgys family's deportation route (Map, Mindaugas Baltrušaitis, 2012). Source: Sound Archives. European Memories of the Gulag.

Media subject to copyright.

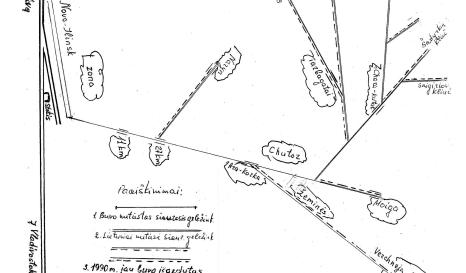

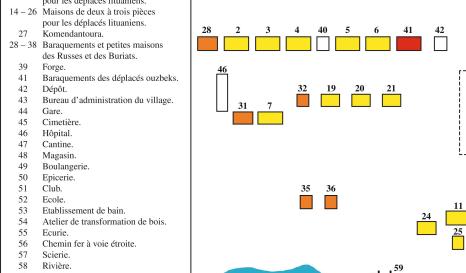

Settlement plan of Zaigrayevsky District, Buryatia (Siberia) (Drawing, Rimgaudas Ruzgys, Undated). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Places where Rimgaudas Ruzgys went, contemporary map (Map, Alain Blum, 2012). Source: Sound Archives. European Memories of the Gulag.

Media subject to copyright.

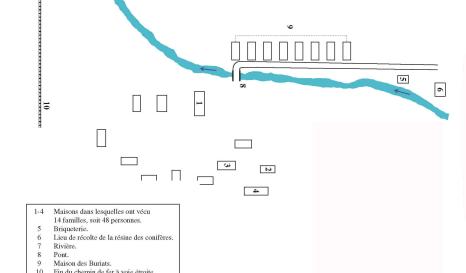

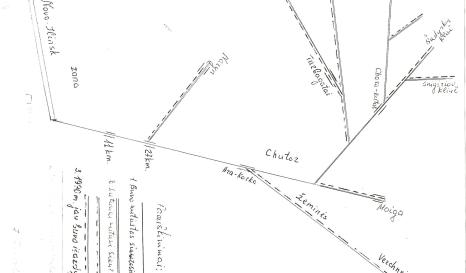

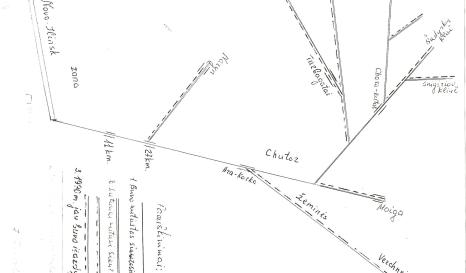

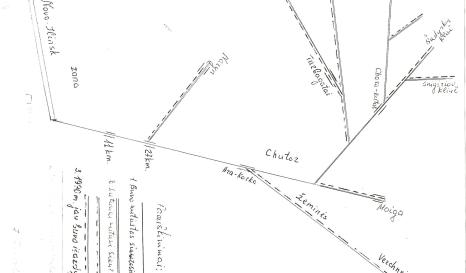

Plan of Khutor village, Buryatia (based on the Rimgaudas Ruzgys design). The village no longer exists (Drawing, S.C. - UMR 5281 - ART-Dev - CNRS, 2011). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

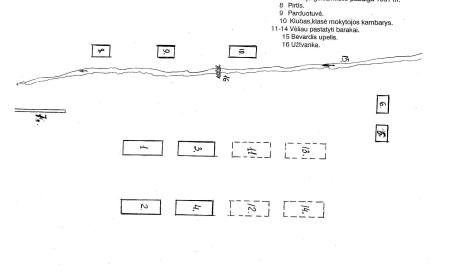

Plan of Moigu village, Buryatia (Siberia) – the village no longer exists (Drawing, Rimgaudas Ruzgys, Undated). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Plan of Khutor village, Buryatia (based on the Rimgaudas Ruzgys design). (Drawing, S.C. - UMR 5281 - ART-Dev - CNRS, 2011). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

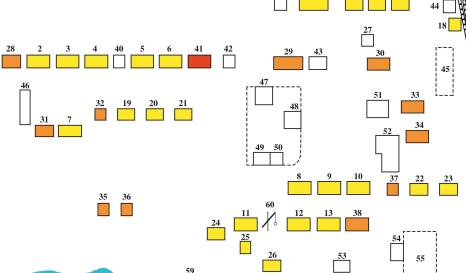

Plan of Khara-Kutul village (legend), where Rimgaudas Ruzgys lived in relegation (Drawing, S.C. - UMR 5281 - ART-Dev - CNRS, 2011). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseTravels of the Ruzgys family

In May 1948, the Ruzgyses, a Lithuanian farming family, were arrested near Šiauliai and deported. After travelling two weeks, the resettler train arrived in Buryatia in Eastern Siberia, south-east of Lake Baikal. Small groups of resettlers were put in open trucks on a narrow-gauge railway and allocated to various villages. The territory was settled by the resettlers along these railways which ran up the valleys of the Yablonovy mountains. The Ruzgys family and fifteen other families were taken to the hamlet of Khutor, which had twenty or so houses. The resettler families moved into four of them.

Before the early arrival of the Siberian winter, the resettlers quickly built a new hut village, Moigua, in the taiga, extending the narrow-gauge railway to the north-east.

The village only lasted a few years, until all the forest in the valley was felled. A new village was built in another well-wooded valley that offered several years of work. Life in this village, Khara-Kutul, populated largely by Lithuanians, was more comfortable: larger houses, basic amenities and services. Of the three villages Rimgaudas Ruzgys lived in, it is the only one that still exists. The Lithuanians moved from being itinerant settlers to residents who could at last take the place over.

Rimgaudas had a great “advantage” over the other resettlers. He was a “free man” because his parents had managed to change his date of birth to make him one year younger. But this free man’s “advantage” turned against him. Adult resettlers were not called up to the army, but Rimgaudas had to leave the village to do his military service in the Soviet Army. He was sent to Khabarovsk on the Chinese frontier. At that point his family moved to Novoilinsk village, their last destination in Siberia before they were set free and could leave, in 1956-1957.

In 1960, after three and a half years’ military service, Rimgaudas Ruzgys returned to Lithuania and settled in Vilnius. In the early 1960s, his parents, brother and sister also moved to Vilnius because they could not return to the family house, now occupied by other people.

-

Three resettler villages.First day in the resettler village

Three resettler villages.First day in the resettler village

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseThree resettler villages.First day in the resettler village

“Then we set off with horses from the narrow-gauge railway to the village. The village was about half a kilometre, a kilometre away. We each carried our own stuff. They took us to a house built the way they are in Siberia, of logs, typical as we later saw. It was divided into four rooms, a corridor and four small rooms. They put five families of us in that house. The first night, we could not lie down or stretch out, there were only the walls and nothing else. The house only had plank partitions to separate it a bit. We lay down as best we could on our bags and got attacked by the bed-bugs. When the bugs attacked we got up and saw they were everywhere on our arms, they were biting everywhere and we did not know where to put ourselves. Everyone was hungry after the journey and no one had had a hot meal. The next morning we all placed stones outside and those who had saucepans or buckets began to cook something to eat, something hot. Those who had something; there was no shop. The first night, when we got into the house, we barricaded the front door.

We thought, you never know, there were strangers around; the local people carried knives because they had been told we were bandits. We shut ourselves in, barricaded on the inside so the local people would not get into the house where we were spending the night. That’s how we moved in.”

-

Three resettler villages.Building the second village

Three resettler villages.Building the second village

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseThree resettler villages.Building the second village

“The place was called Moyga. As usual out there, they had only built a few huts, but everyone had to be housed. So they dumped three or four families per room, as many as they could. In the middle of the room there was a barrel with holes in it and a chimney coming out to heat the inside a bit.

The door had no hallway, it opened directly outside. When we started heating in winter, it was about –40°C outside, bitter cold. Inside, the walls were of unseasoned wood and the water condensed and ran down them; you had drops falling on your head. We had no floor because there was no sawmill.

So we had to make floor planks by splitting logs. We split the logs into planks, which we used to make a sort of floor. The same for the ceiling: we had to cover it up a bit and we used that type of plank. We took great pine logs, two or three metres long with no branches because they were easier to split. We put a layer of earth on the floor to make it warmer. When they built the huts, they didn’t dig any foundations. They built on tree stumps or posts. Instead of foundations, we piled up about a metre of earth against the sides up to the windows so the cold would not get in from below. That’s how we spent our first winter.”

-

Three resettler villages.Building the third village

Three resettler villages.Building the third village

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseThree resettler villages.Building the third village

“The village did not last long, perhaps only three years. We cut down all the forest, they may have got their sums wrong, they didn’t realise the Lithuanians were so hardworking and would work so quickly. When we’d finished cutting down the forest, it was too far away, the narrow-gauge railway had reached the mountains and couldn’t go any further. They had to transfer to another valley, so they started to build a new village in an area where there were plenty of forests. It was only for another few years.”

-

Work: building the railway

Work: building the railway

Close

CloseWork: building the railway

“The first winter, people cut logs. Along with building a new village and huts in the middle of the forest, we had to build a narrow-gauge railway. The Lithuanians began to build the railway. But logs had to be brought from the mountains to the railway. In the early years, we used oxen, we had no horses, but there weren’t many oxen either.

So the Lithuanians dragged the logs themselves. It was like that picture we saw once, ‘Burlaks [barge-haulers] on the Volga’.”

-

Life in a deportees’ village, after Stalin died

Life in a deportees’ village, after Stalin died

Rimgaudas Ruzgys riding his new motorbike (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

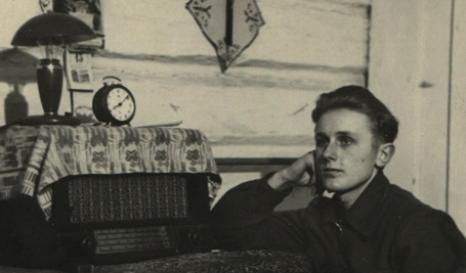

A “window” onto the free world: Rimgaudas Ruzgys listens illegally to Voice of America (Photograph, Anonymous, 1957). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A wedding in a deportees’ village in Buryatia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A summer Sunday in deportation in Buryatia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953-1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

The village theatre group in Khara-Kutul. Rimgaudas Ruzgys and his brother (3rd and 1st from right) (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A theatre group in a deportees’ village (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Young deportees (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

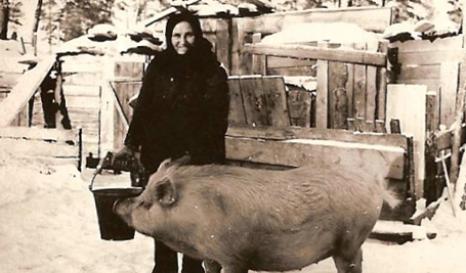

Rimgaudas’s Ruzgys mother on her farm plot (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseLife in a deportees’ village, after Stalin died

-

Life after the death of Stalin

Life after the death of Stalin

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseLife after the death of Stalin

“Then, after Stalin died, things got a bit better. The young Lithuanians started buying bikes… Our family bought a small K125 motorbike. While I was still a youngster, we went to Ulan-Ude, the capital, 150 km away, to buy that motorbike. I came back on it, with no licence or experience in riding one, through the fields and the forest… we were four or five mates who bought the bikes and rode them back.

Later, when we were 15 or 16, after Stalin died, we started organising activities, dancing traditional dances, and the girls made national costumes. Everyone did what they could, as well as they could. We put on shows in our village, because a lot of people had lived there for quite a time. Some people managed to get instruments and began to play them; little bands were formed. There were older people and younger ones, some with accordions, other with violins, percussion, and girls playing the guitar. We would gather near the huts in the evening and dance on the bare earth. We even took part in an outside event, a regional festival; it was an excursion. Life changed a little.”

-

“I won’t go back home, I’ll go somewhere in Siberia.”

“I won’t go back home, I’ll go somewhere in Siberia.”

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by A. Blum & E. Koustova, 17/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

Close“I won’t go back home, I’ll go somewhere in Siberia.”