BioGraphy

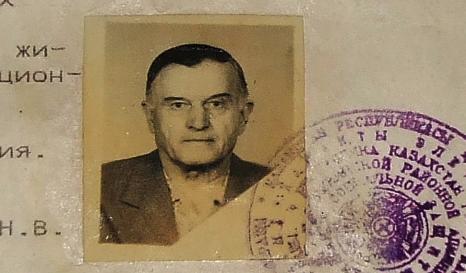

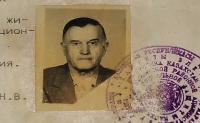

Andrei OZEROVSKI

Andrei Ozerovski was born in 1914 in Lutsk, the administrative capital of Volhynia, then in the east of Russian Poland. During his life he crossed the continent of Eurasia to find himself in Karaganda, Kazakhstan, where he then enjoyed his retirement. He was a primary school teacher and during the war became a sympathising witness of Polish and Ukrainian resistance to the Nazi occupants and the troops of the Red Army.

He was arrested in 1944 on a charge of “anti-Soviet activism” and sent first to the Bryansk penal colony near Belarus, where he survived an extremely harsh regime. He was then sent to Arzamas 16 (now Sarov), where he helped build the closed town at the heart of Soviet research on the atomic bomb. In 1947 he was deported to Kazakhstan, to the vast farm camp of Karaganda, the Karlag, cutting him off from his native region. Some months after arriving at the Karlag he was sent to complete his sentence in the Steplag camp, out in the remote arid steppes. Like the other prisoners he worked at mining copper from the deposits of the mineral-rich region.

Released in 1954, he returned to Karaganda, a coal town, where he settled and went back to mining, a world he liked and where he made his career. He integrated into Soviet society in Karaganda, alongside a population of displaced persons of all sorts, those expelled by Stalinist society and workers attracted by incentives to advance the prosperity of the town built from scratch in the 1930s. He kept some contact with his native region, part of Ukraine since 1939, by regularly going back but said that his main roots were not there.

The interview with Andrei Ozerovski was conducted in 2009 by Isabelle Ohayon et Elena Zimovina.