BioGraphy

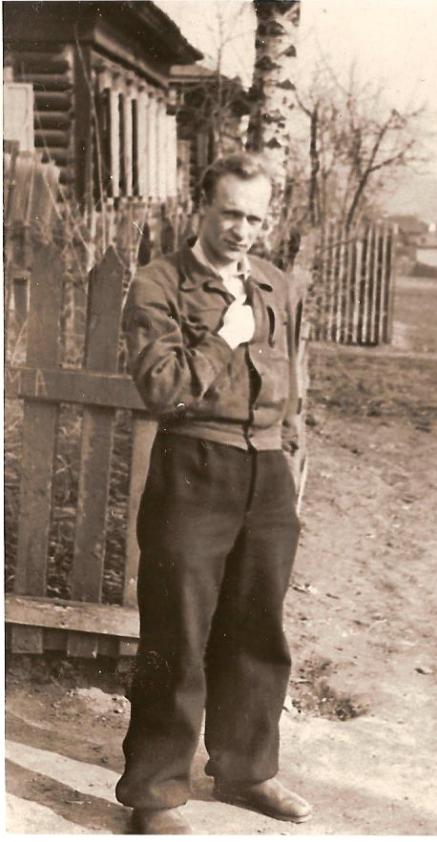

Antanas PANAVAS

Antanas Panavas was born in the village of Grybėnai, eastern Lithuania, in 1926. His parents were farmers and his family “was better off than the others”. After secondary school in Vilnius, in 1945 he was suspected of anti-Soviet activities, arrested and, without being sentenced, sent to work in the Vorkuta camp in the Komi Republic. After two years, with no evidence of his guilt, he was released. However, his freedom did not last long: in 1951, shortly after arriving in Vilnius for the fourth year of his architecture course, he heard that his family had been arrested during the last deportation of kulaks. That evening, he voluntarily joined them at the station to be deported with them.

The family was exiled to the Krasnoyarsk region and the young architecture student became a kolkhoz worker. After Stalin’s death in 1953, an understanding kommandant allowed him to go and work in town, in Krasnoyarsk. In a draughtsman’s office where he was working with people of thirteen different nationalities, Antanas gained a training in building construction: “It was a school for the whole of life”. As soon as he returned to Vilnius in 1958 he completed his course and worked as an architect on major projects in Lithuania.

The skills he learnt during deportation influenced a number of his buildings. For example, the church that Antanas built for his previous German fellow deportees that remains as a symbol of friendship between the many nationalities of the Gulag.

The interview with Antanas Panavas was conducted in 2009 by Jurgita Mačiulytė.