BioGraphy

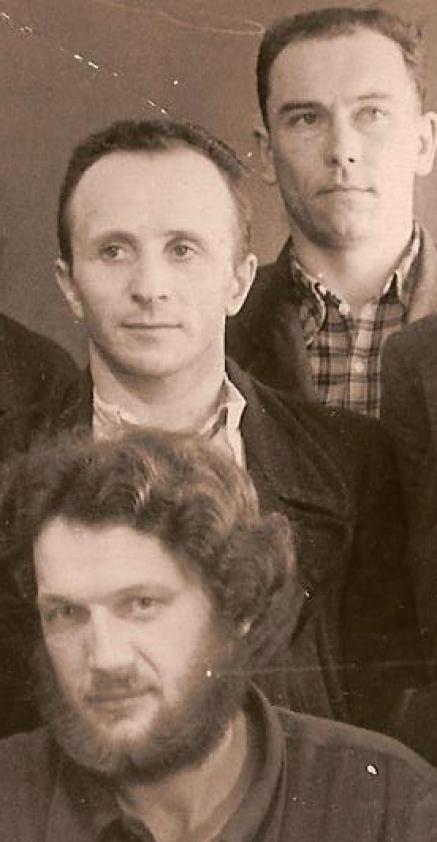

Antanas PETRIKONIS

Antanas Petrikonis was born in 1928 in the village of Mociškėnai in southern Lithuania. His family was of peasant origin, poor and very patriotic. After the war, when the Soviets returned, Antanas joined the armed resistance, first helping them and then, in 1948, fighting under the codename “Laivas [ship]”. In 1951, he was arrested in the bunker built near the house where he was born, and sentenced to 25 years’ forced labour. After spending time in various prisons, he was transferred to Kengir camp in the Steplag in Kazakhstan, where he joined the Lithuanian underground. He took part in the uprising in the summer of 1954. After the uprising, he was transferred to the Berlag in Kolyma and then to the Ozerlag in the Irkutsk region. In 1956, his case was reviewed and his sentence halved. In 1960, after another case review, he was released but not allowed to return to Lithuania. He returned anyway and through the incompetence of a young civil servant managed to acquire residence in his native village.

After his marriage, despite huge difficulties, he gained a residence permit for Kaunas, where his wife lived. He still lives there.

He often thinks about his country’s fate: “Lithuania lost too much blood after the war. If those 26,000 men who died in the forests – most of them young, men of ideas, patriots – had had children, the face of Lithuania today would be different. But they did defend Lithuania’s honour.”

The interview with Antanas Petrikonis was conducted in 2009 by Jurgita Mačiulytė.