BioGraphy

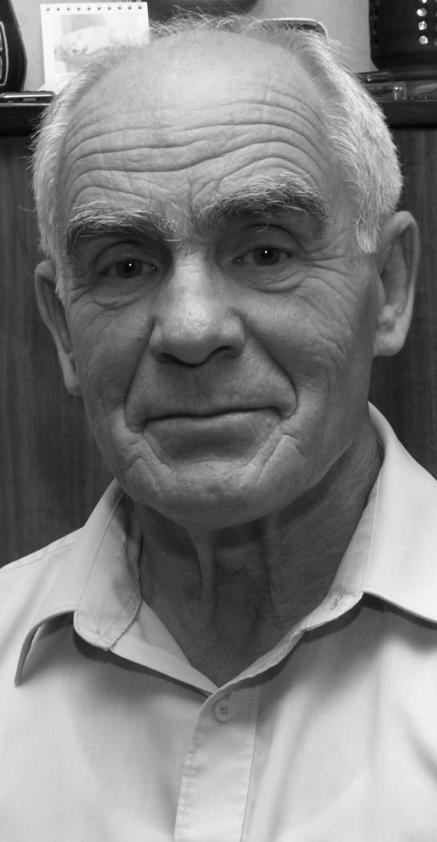

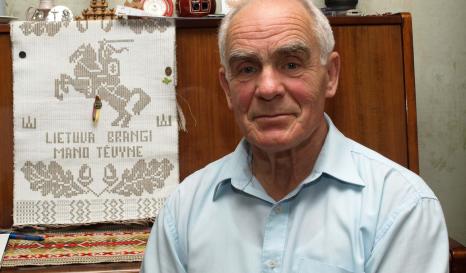

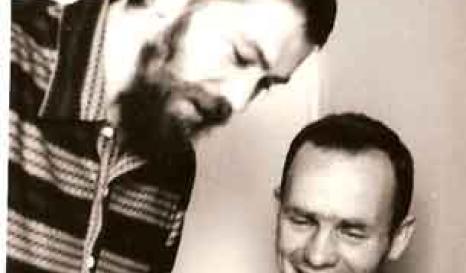

Jonas VOLUNGEVIČIUS

Jonas Volungevičius was born in the village of Kabeliai in southern Lithuania in 1940. When he was born, his father was serving a ten-year sentence as a political prisoner. Jonas only saw his father once, when he visited the prison in Belarus with his mother. He and his mother were evicted from their home by the Soviet authorities and for years they lived in the abandoned houses of deported families.

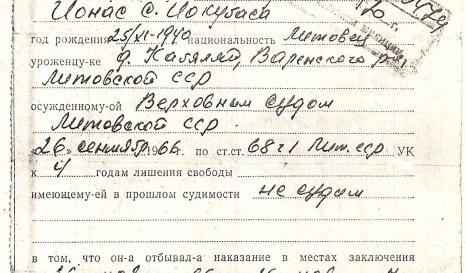

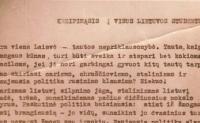

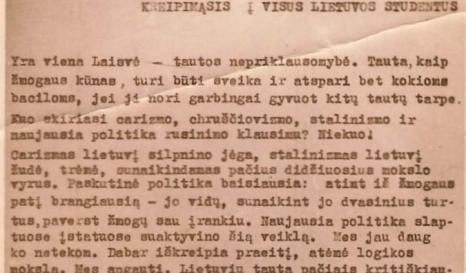

After secondary school, Jonas enrolled at the music conservatoire and worked at the same time. In Vilnius he met other young people “concerned by Lithuania’s destiny” and in 1963 he was already taking part in activities against Soviet control by organising various underground demonstrations (anti-Soviet letters for Baltic students, distribution of anti-Soviet cartoons, etc.). In 1966, he was arrested and sentenced to four years’ forced labour in the camps in Mordovia. On his return, he did not “settle” and resumed his anti-Soviet activities. In 1978, with other dissidents, he set up Lietuvos laisvės lyga (League for the Liberty of Lithuania). Harassed by the KGB, he continued his fight until Lithuanian independence in 1990.

The interview with Jonas Volungevičius was conducted in 2009 by Jurgita Mačiulytė.