BioGraphy

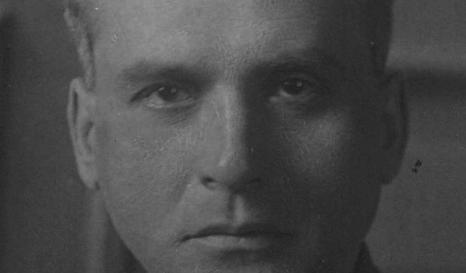

Vladimir SIDERSKI

Vladimir Siderski was born in 1926. He was the son of a revolutionary who held high political and administrative offices in Ukraine and was shot in 1937. So he was considered to be the son of an enemy of the people. He saw the start of the war in Kiev and was evacuated to Siberia, and then to Tomsk and Moscow. He left for Siberia without his mother, because she was the wife of an enemy of the people and, as a “friend of the Germans”, was not allowed to leave the city. She died there of typhus.

In April 1945, he raised questions about the Stalin purges, was arrested and sentenced to labour camp. He was sent to Rybinsk and then to Pechora, where he spent several years. He thinks he “was lucky”, because after a while he began to enjoy better living conditions than the other prisoners.

When he was released in 1951, he returned to Ukraine but was forbidden to reside in Kiev, other major cities in Ukraine and border areas. He got a job in Chernigov, although his past occasionally caught up with him. Then he returned to Kiev and is now a member of the rehabilitation commission for purge victims.

The interview with Vladimir Siderski was conducted in 2009 by Alain Blum.