ToPics

Languages

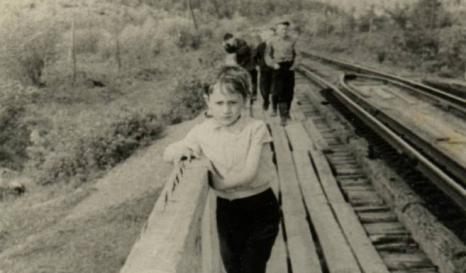

Learning, speaking and even forgetting languages are major markers of the experience of deportation.

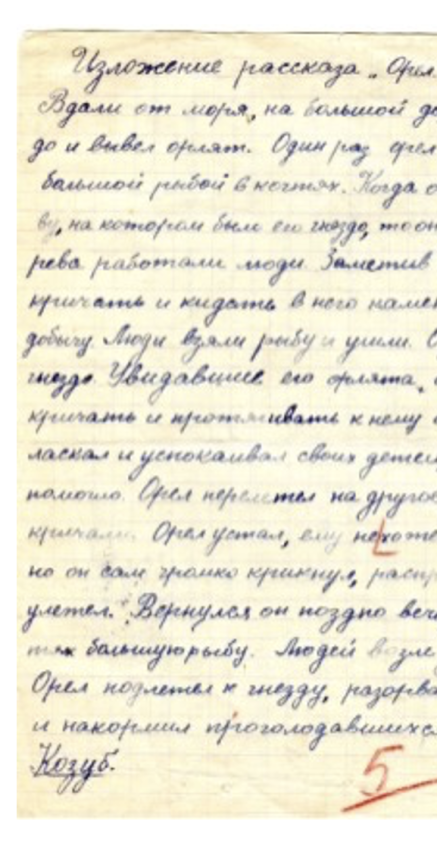

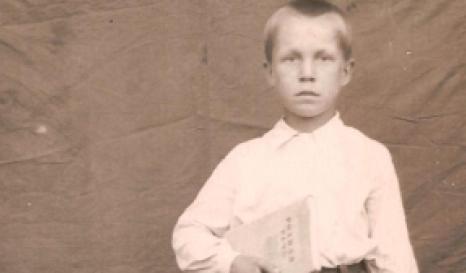

Deportation often meant encountering new languages, either Russian, which children learnt at school and spoke among themselves, or those of other deportee communities, when resettlers and prisoners sometimes learnt each other’s languages.

But the issue also arose of preserving (or learning in the case of the youngest children) one’s native language or languages, which in many families symbolised their identity, a link to a culture or land, and a heritage to be passed on to younger people. There might be more than one language, because these communities had lived in a variety of places. In Lithuania, for example, they may have spoken Lithuanian, Yiddish, Polish, Russian or Belarusian. Preserving and passing on these languages was also seen as a way of resisting Russification or Sovietisation.

For those who opted for it on release, returning home also meant returning to a language. Those deported when very young, or born in deportation, often had to re-learn or improve a language learnt only colloquially in private.

Then after returning and settling in again, came the question of passing on to future generations these many languages that carried so much personal, family and political history.

French original: Jeanne Gissinger, translated by Roger Depledge