European Memories

of the Gulag

ToPics

Childhood IN THE GULAG

After the Red Army’s advance into Eastern Poland and the Baltic states, waves of deportation begin in 1940. Families are sent with their children to remote villages in Siberia and Central Asia; children are born there. Although some go to school, most have to work. Some spend time in orphanages.

From 1944, as the Soviets move back towards the west, hundreds of thousands of farming families are deported and a large number of children and adolescents are arrested, interrogated, found guilty of “nationalism” or “espionage” and sentenced to long periods of forced labour in the camps of the Gulag.

Deportation and life in the camp become the background to the early socialisation of an entire generation of Europeans and leave a mark on their childhood.

The voices and stories of the witnesses reveal the unique intensity of an experience in which fear, pain, hunger and cold are mixed with amazement at discovering a new country, sharing games and moments of happiness; an experience that they now see as a decisive lesson for their entire lives.

Marta Craveri and Anne-Marie Losonczy

-

Silva Linarte tells of her meeting with the wolves

Silva Linarte tells of her meeting with the wolves

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by A. Blum & J. Denis, 13/01/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseSilva Linarte tells of her meeting with the wolves

Audio available /“I remember the school was 18 km away, we had to walk there, not every day, of course, but all the same. We had to walk through the taiga in winter with snowstorms, the cold and the wolves.

And one day, we were not far from the village of Ulyukol [Улюкол]. We children, Lithuanians and Latvians, were walking along. And then we saw some little lights in the distance. They were a long way a way and all round us. We didn’t realise what they were. We saw that the circle was closing in. And when it was near us, we saw that it was wolves. Everyone was very afraid. We started screaming, not to make them go away, but because we were terrified. We screamed with fear and the wolves began to move back. The circle became wider again. They didn’t go away immediately. That was their system: they widened the circle before they went.

Gosh, we were afraid!”

-

Irena Ašmontaitė – Giedrienė in an orphanage

Irena Ašmontaitė – Giedrienė in an orphanage

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by J. Mačiulytė, 27/10/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseIrena Ašmontaitė – Giedrienė in an orphanage

-

Elena Talanina : " At the age of 14, I was working not 8 but 16 hours a day! "

Elena Talanina : " At the age of 14, I was working not 8 but 16 hours a day! "

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 27/08/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseElena Talanina : " At the age of 14, I was working not 8 but 16 hours a day! "

-

Adam Chwaliński sawing lumber

Adam Chwaliński sawing lumber

Source: Interview conducted in Poland by A. Niewiedzial, 23/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseAdam Chwaliński sawing lumber

In these two extracts, Adam Chwaliński describes how at the age of eleven and a half he worked sawing lumber in the forests of Siberia.

-

Adam Chwaliński work in the taiga

Adam Chwaliński work in the taiga

Source: Interview conducted in Poland by A. Niewiedzial, 23/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseAdam Chwaliński work in the taiga

-

Klara Hartmann describes her interrogations

Klara Hartmann describes her interrogations

Source: Interview conducted in Hungary by A.-M. Losonczy, 01/09/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseKlara Hartmann describes her interrogations

“I was in prison, locked up with Russians. So I couldn’t really talk either. Basically, I didn’t realise what was happening to me, where I was, what I was doing there, what they were going to do with me. After two or three months, they transferred me to a single cell. And then the interrogations started, to get me to admit that I was a spy and who I was working for. There was an interpreter, a soldier from Transcarpathia who spoke Hungarian fluently. He said I should confess, because if I stretched it out I would die in prison. But I told him, “I haven’t been a spy. I don’t know what it means.” He insisted I should say I had and this nagging and pressure went on a long time. Because the interrogations were at night, in the daytime, they wouldn’t let me sleep. I had to stay upright in the cell all day. And a soldier would look through the spyhole to see I didn’t lie down but kept walking. Altogether, they were torturing me that way to get me to quickly say what they wanted to hear. In the end I couldn’t do anything. I was completely exhausted: they wouldn’t let me sleep or eat. So I said that indeed I was a spy, but I also had to sign a paper saying so. I also had to say where I’d been trained, in which school, who my teachers were, etc. And I couldn’t give any answers to that because I wasn’t a spy and I had no idea. And with the advice of the interpreter they wrote down what they could. Then some months passed. And just before Christmas I was called into the office and I had to sign that I had got ten years. The interpreter told me that I was being sent for ten years’ forced labour, but I shouldn’t be afraid because it would be all right and I could even survive perhaps, and after ten years I would be released and would live in Russia with a job and a flat and things would pass. I was almost glad.

I can’t tell you or, what shall I say, I can’t describe the things that happened to me in that prison because there were all sorts: sometimes I was put under a tap with drops of water falling on my head all the time. They would torture me that way with cold water. They called in the “box”. I nearly froze to death. Then they would take me out to go for interrogation.”

-

“Repatriated” Latvian and Estonian orphans

“Repatriated” Latvian and Estonian orphans

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by A. Blum & J. Denis, 13/01/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

Close“Repatriated” Latvian and Estonian orphans

In 1946, at the instigation of the Latvian Ministry of Education, the “orphans and half-orphans” in the special settlements were allowed to return to Latvia. Many children had indeed lost one of their parents during the war and for the surviving mothers, sending them back to Latvia, for all the shock of separation, meant increasing their chances of survival.

So some 1,300 children, mostly Latvian but with a few Estonians, returned to the Baltic republics in 1946-1947. Often the escapees could not believe that their return was legal, although it is recorded in the Soviet archives, and put it down to a combination of luck and heroic individual initiative. For Silva Linarte and her sisters, arriving at the orphanage in Riga meant the discovery of (relative) abundance. When the children arrived after their exhausting journey from Siberia, they distrusted the food they were offered. The medical officer was the only one to understand and suggested cooking them potatoes, the only food they knew.

For these children, this return – ahead of other categories of resettlers – was a shock that is graven in their memories, the rediscovery of their homeland. Austra Zalcmane, her sister Lilija Kaione and Peep Varju benefited from this same exceptional treatment.

-

Marytė Kontrimaitė : Homesickness and patriotism in Siberia

Marytė Kontrimaitė : Homesickness and patriotism in Siberia

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by E. Koustova & A. Blum, 11/06/2011.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseMarytė Kontrimaitė : Homesickness and patriotism in Siberia

In Siberia, the Lithuanians would get together and sing “Let us go back to our motherland” and read poems. Marytė Kontrimaitė’s mother often spoke to her daughter of their traditions and legends. The little girl built up an idyllic image of her motherland.

-

Peep Varju: Harsh life in the orphanage

Peep Varju: Harsh life in the orphanage

Source: Interview conducted in Estonia by M. Craveri & J. Denis, 19/01/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

ClosePeep Varju: Harsh life in the orphanage

Audio available / -

Antanas Kybartas recalls Siberian nature and his childhood in deportation

Antanas Kybartas recalls Siberian nature and his childhood in deportation

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by J. Mačiulytė, 28/10/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseAntanas Kybartas recalls Siberian nature and his childhood in deportation

Audio available /In this excerpt, Antanas Kybartas talks about his childhood memories in Siberia: nature, other children, languages.

-

An orphenage in Irkutsk

An orphenage in Irkutsk

Eastern Siberian newsreel (Eastern Siberian newsreels studio, Circa 1950-1960). Source : Irkutsk Regional Film Archive.

Media subject to copyright

CloseAn orphenage in Irkutsk

An orphanage in Irkutsk

Propaganda picture of a Soviet orphanage, taken from an Eastern Siberian newsreel, far from the actual conditions there.

-

Growing up in the Gulag

Growing up in the Gulag

Child working in the forest (Photograph, Anonymous, Undated). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

Irina Tarnavska (right) in deportation with her sister and grandmother (Photograph, Anonymous, 1951). Source: Irina Tarnavska's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Irina Tarnavska (below right) in deportation (Photograph, Anonymous, 1951). Source: Irina Tarnavska's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Irina Tarnavska (left) with her father and sisters in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1951). Source: Irina Tarnavska's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Families of resettlers in the wagon taking them to the Krasnoyarsk region in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1951). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

Siiri Raitar (top right), in her class in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1951). Source: Siiri Raitar's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

An Estonian family in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1949-1955). Source: Siiri Raitar's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A family of resettlers (Photograph, Anonymous, 1952). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

Family of a Lithuanian resistance fighter resettled in the Irkutsk region in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1949). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

Juliana Zarchi (centre) at school in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1950). Source: Juliana Zarchi's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Pupils at Khara Koutoul school, Autonomous Republic of Buryatia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1954). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys’s mother and sister Regina (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys’s mother and sister with friends (Photograph, Anonymous, 1953-1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

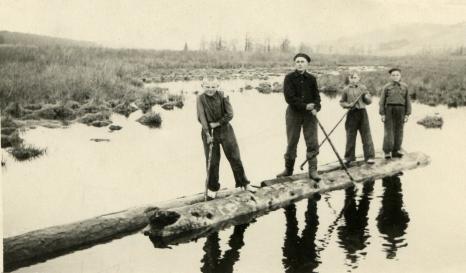

Rimgaudas Ruzgys with children using tree-trunks to cross swamps (Photograph, Anonymous, 1955). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

An orphanage for Polish children (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1943). Source: Janina Borysewicz's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Funeral of Danuta Woyciechwska’s sister in Kazakhstan (Photograph, Anonymous, 1940-1944). Source: Danuta Wojciechowska's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Siiri Raitar (top, 2nd left), first year at school in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1949-1950). Source: Siiri Raitar's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Family of a Lithuanian resistance fighter resettled in the Irkutsk region in Siberia (Photograph, Anonymous, 1950). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseGrowing up in the Gulag

A childhood with the shock of leaving home, the journey without end, the cold, the hunger, the fear, work to have an extra ration card, but also the discovery of an unknown natural world, school, friendship and games shared: that was how children grew up in the Gulag.

-

In a Polish orphanage

In a Polish orphanage

Henry Welch and his friend Simka at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Henry Welch — From deportation to exile around the world (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Children at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Henry Welch (right) and a classmate at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Children at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A child at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A girl at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Klara, a teacher at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan and friend of Henry Welch’s mother (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Yurek at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Simka, his best friend at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A boy at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A boy at the Leninabad orphanage in Tajikistan (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1945). Source: Henry Welch's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseIn a Polish orphanage

When the amnesty for “Polish citizens present on Soviet territory” was granted in August 1941, the Welches left Arkhangelsk for Kyrgyzstan, then Kazakhstan and finally Leninabad [Khujand] in Tajikistan. There they found a comfortable house and for the first time, at the age of 9, Henry went to school. Because she could not look after him, his mother placed him in a Polish orphanage, but he has happy memories of that time: “It was a very important part of my life. First of all, I was a child among children. Before that, I spent all of my time only with grown ups.”

Even today, he keeps photos of his orphanage friends in his study in his flat in Rome... -

Alexandra Belomestnykh, as a child, follows a plough

Alexandra Belomestnykh, as a child, follows a plough

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by E. Koustova, L. Salakhova & A. Blum, 30/08/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseAlexandra Belomestnykh, as a child, follows a plough