European Memories

of the Gulag

ToPics

The journey to resettlment

From arrest to resettlment, the deported prisoners’ journeys took a surprisingly similar shape. They would be arrested in a village and often taken by cart to the nearest railway halt, where others would be waiting; nearly all the stories begin like that. The long train was made up of cattle trucks, not always with bedframes; sometimes people had to sit or lie on the floor. All ages and sexes were crammed together. And then the journey was long, very long with no place of the destination given at the start.

Arrival was sudden, unexpected. The railway halt was usually small, in the middle of nowhere, but that was not the end of the journey. The deported prisoners then had to continue by carriage or lorry to the final destination, or wait a while in sheds until they were fetched. Dozens of kilometres before they reached the first stopping point of deportation.

-

Arrest and journey

Arrest and journey

Source: Interview conducted in Russia by A. Blum & I. Tcherneva, 25/07/2015.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseArrest and journey

Naum Kleiman’s family were deported on 6 July 1949. He recalls that the lieutenant in charge of the detachment was highly attentive and helped them. He describes the journey to Guryevsk. Left the train in Belova, travelled on to Stalinsk (now Novokuznetsk). Then took a narrow-gauge line to Guryevsk, then on to a small abandoned village, Yunka, where there were disused gold mines.

He emphasises that they were lucky to be on the second train and not the first, because the first was sent to Irkutsk region, much harsher, whereas their train, the second, was sent to the Kuzbass, where life was less hard.

-

The deported prisoners’ journeys

The deported prisoners’ journeys

The deported prisoners’ journeys

From arrest to relegation, the deported prisoners’ journeys took a surprisingly similar shape. They would be arrested in a village and often taken by cart to the nearest railway halt, where others would be waiting; nearly all the stories begin like that. The long train was made up of cattle trucks, not always with bedframes; sometimes people had to sit or lie on the floor. All ages and sexes were crammed together. And then the journey was long, very long with no place of the destination given at the start.

Arrival was sudden, unexpected. The railway halt was usually small, in the middle of nowhere, but that was not the end of the journey. Either they continued immediately by car or lorry to their final destination. Or the deportees waited for a time in huts until they were fetched.CloseForty or fifty kilometres more before they arrived in the place that would be the first stage of their resettlement. During the train journey, because the line was single-track, they would wait for ages at a station to let another train through in the other direction. The train would stop at some forsaken station in Siberia and then reverse along a route that never seemed to be direct.

The men and women organised themselves, set aside a corner of the wagon as a lavatory, with a hole in the floor and a bucket. They tried to preserve some sort of privacy. Although the children were not embarrassed, they could tell the women were. The doors were kept shut; there might be a small window that let in a glimpse of the countryside. Some had brought food; others tried to get some when the train stopped. Hot water was essential, and this was given out in stations, when one of the passengers would go and fetch it, without moving too far from the train, under the watch of the escort.

The escort soldiers only appeared when the train stopped and the wagon doors opened a little. They were not particularly violent in their behaviour, but the children could hear them shoot if anyone tried to escape. Sometimes the escapees managed to disappear into the forest. No one, of course, would ever know what became of them.

During this journey into the unknown and the uncertain, landmarks like the crossing of a large river, the passage through the Ural mountains and the first sight of the taiga took on great importance. Everyone had their own idea about where they were and what the changing landscape meant. Among these similar stories, some differences do emerge. The journeys in 1941 and 1944 were clearly more painful, with ever-present hunger and exhaustion, than those in 1949, years after the war.

These stories may also be compared with the first massive deportations during the collectivisation of 1929-1930, which were often improvised. A “deportation-abandonment” (Nicolas Werth) when the resettlers were sometimes simply dumped in the countryside. What these witnesses relate was generally not so bad. The organisation was better; they were received, even in poor conditions. The instructions published by the interior ministry departments in charge of resettlement do actually correspond fairly well to what the witnesses relate now.

Alain Blum

-

Rafail Rozental’s testimony

Rafail Rozental’s testimony

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by J. Denis, M. Craveri & V. Nivelon, 11/06/2008.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseRafail Rozental’s testimony

Audio available /"[...] I remember… When we were taken to Šķirotava station, there were goods trucks people were pushed into. That same evening, they separated the men and women and I can still hear those women weeping. What I remember most from the long journey to Siberia is the smell of the kipiatok, the boiling water they gave us to drink at stations. I remember the soldiers between the trucks. It was summer, it was warm and the journey was fairly comfortable. True, we were being deported, but my mother was with me and my father, well, he had already been taken away."

-

Guessing the final destination – Kasimir Gendels’s obsession

Guessing the final destination – Kasimir Gendels’s obsession

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by J. Denis & A. Blum, 13/01/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseGuessing the final destination – Kasimir Gendels’s obsession

After miraculously finding his father again before getting into the wagon, Kasimir Gendels and his family were sent to the East with other deportees. With no information about the final destination, the group of deportees attempted to find out where they were from the successive directions the train took: northwards – were we going to the dreadful mines in the Great North? Southwards – would it be Kazakhstan?

-

The “Russian Hell”

The “Russian Hell”

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by J. Denis, 17/06/2008.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseThe “Russian Hell”

On the train, Austra Zalcmane heard the adults cursing Russia, which they compared to Hell. So in the girl’s mind, the idea formed that the resettlers were to be thrown into a world of flames. She was terrified of arriving in Russia.

-

The soldiers’ surveillance relaxes

The soldiers’ surveillance relaxes

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by J. Denis & A. Blum, 13/01/2009.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseThe soldiers’ surveillance relaxes

Once through the Urals, the soldiers stopped bothering to keep a close eye on the train that Kasimirs Gendels and his family were travelling on – where could they escape to?

-

Austra’s boat journey

Austra’s boat journey

Source: Interview conducted in Latvia by J. Denis, 17/06/2008.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseAustra’s boat journey

River transport was also a feature of the deportees’ journey to their final destination. When they arrived in Krasnoyarsk, Austra Zalcmane and the others got on a boat and travelled upstream to further destinations. During the journey, they noticed a leak in the boat and were all afraid of sinking and drowning.

-

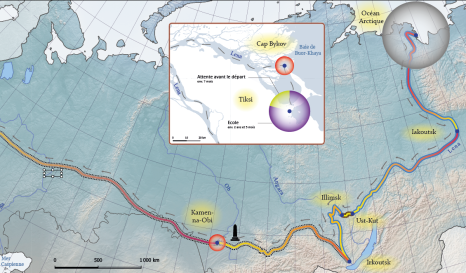

A long journey to the Laptev Sea

A long journey to the Laptev Sea

Source: Interview conducted in Lithuania by M. Craveri, 30/04/2010.

Licence CC BY-NC-ND.

CloseA long journey to the Laptev Sea

Audio available /David Jozefovich, deported to Altai, was then deported further beyond the Arctic Circle.

(abridged—full version with David Josefovich’s biography) -

Lorries on the frozen River Lena

Lorries on the frozen River Lena

Eastern Siberian newsreel (Film, Eastern Siberian newsreels studio, Circa 1950-1960). Source : Irkutsk Regional Film Archive.

Media subject to copyright

CloseLorries on the frozen River Lena

This clip from an Eastern Siberian newsreel is from 1948. It does not show resettlers but rather the atmosphere of these Siberian regions where in winter traffic crossed the ice on Lake Baikal and the rivers that flow through the region.

-

Forms of transport

Forms of transport

Ox-cart (Photograph, Anonymous, 1950). Source: Valli Arrak's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Bronius Zlatkus in front of a lorry (Photograph, Anonymous, circa 1950). Source: Bronius Zlatkus's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

Damaged lorry in a Siberian logging area (Photograph, Anonymous, Undated). Source: Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.

Media subject to copyright.

Rimgaudas Ruzgys and his motorbike (Photograph, Anonymous, 1955). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

A train taking resettlers to a wedding (Photograph, Anonymous, 1956). Source: Rimgaudas Ruzgys's Personal archive.

Media subject to copyright.

CloseForms of transport

These photographs shown here were generally not taken at the start of resettlement but later. They show common forms of transport in Siberian villages in the late 1940s and 1950s. There are none, however, of the boats that followed the rivers to the north, where there were no railway lines.