ToPics

Places OF RESETTLEMENT

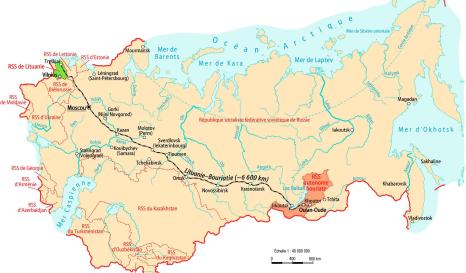

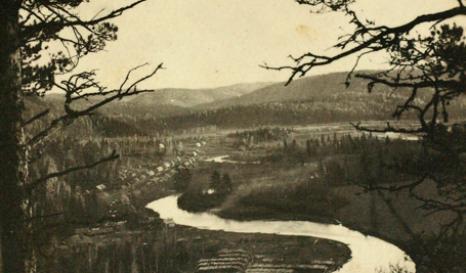

Within a few hours, the deportees left the farmhouse or the town flat where they lived and were loaded onto cattle wagons. They stayed there for a long, uncomfortable journey to places of whose location and nature they knew nothing.

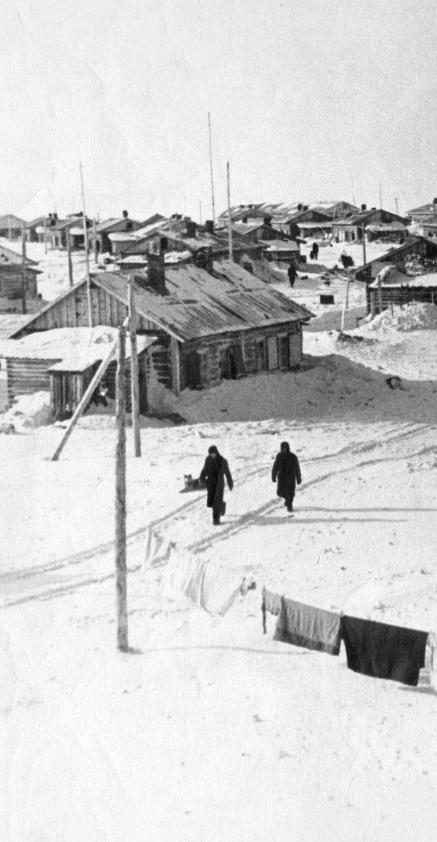

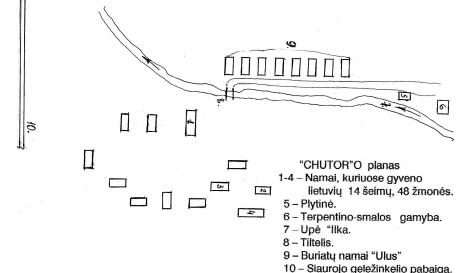

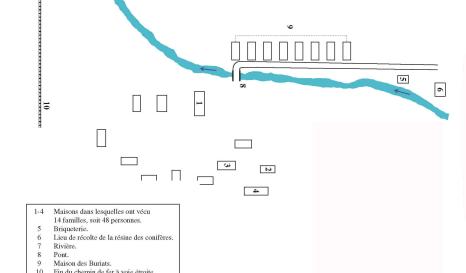

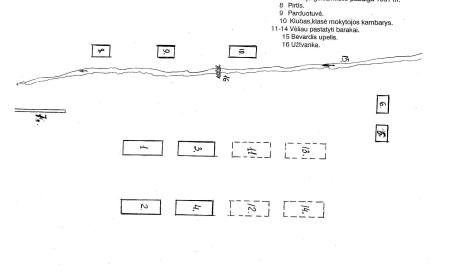

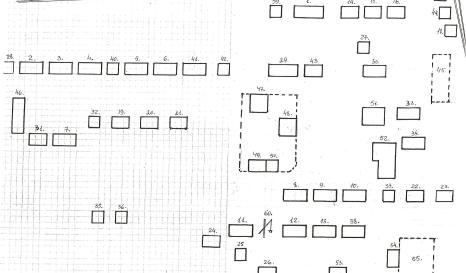

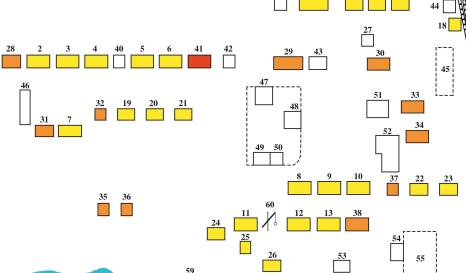

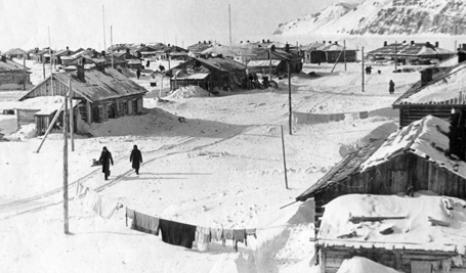

When they arrived, there was often nothing planned for permanent settlement. They were crowded into huts, the buildings typical of the Soviet prison world and also of workers’ accommodation. Some of them lived in houses abandoned by their former occupants, who had themselves been purged or had moved elsewhere. Some were abandoned with nowhere to live but an old cowshed and had to quickly build zemlyanki {half-buried temporary shelters to protect against the cold} which they learnt about from the locals. In this way they managed to get through the winter before they could build more permanent housing or try to rent a room or part of a room from local people.

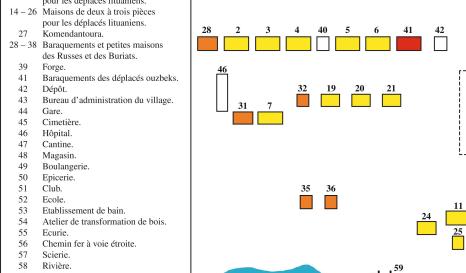

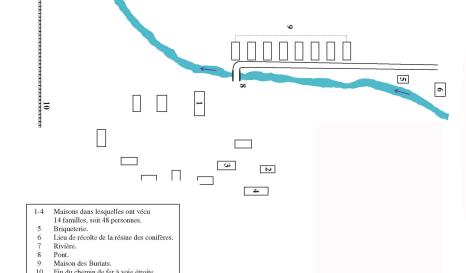

After a few months, the new villages of huts built with outdated tools and temporary materials – cement replaced by moss – appeared in the Siberian landscape. Over the years these resettler villages developed: houses replaced huts, and schools, culture clubs, canteens, etc. appeared.

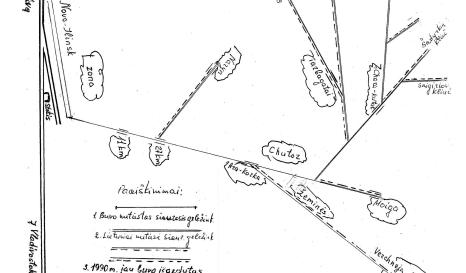

When they moved out in the late 1950s some villages were deserted and the resettler cemeteries are the only memorials of these purges.