European Memories

of the Gulag

ToPics

Setting the pattern for “special settlements”

More than one hundred operations of deportation were undertaken during the Stalin period, but the largest by far was the first mass deportation of Soviet peasants. In 1930 and 1931, more than 1,800,000 kulaks allegedly hostile to collectivisation were “exported” from grain-rich regions to the inhospitable lands of the Russian Great North, Urals, Siberia and Kazakhstan. This special colonisation, as the police called it, was nothing other than a punitive colonisation intended to exert control over the enemy and the territory.

The territories annexed by the USSR – 1939-1941

Under the German-Soviet Pact in August 1939 and its secret clauses on dividing Central and Eastern Europe between the two new allies, Stalin’s USSR began in 1939 and 1940 a new phase of expansion towards the west. The Sovietisation of the new territories involved purges of the former elites and other counter-revolutionary “socially alien elements”, etc.

The territories annexed to the USSR, 1944-1952

After the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in February 1943 and the Red Army’s advance west, further deportations were organised.

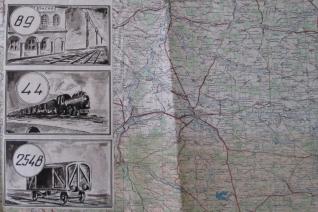

The journey to resettlment

From arrest to resettlment, the deported prisoners’ journeys took a surprisingly similar shape. They would be arrested in a village and often taken by cart to the nearest railway halt, where others would be waiting; nearly all the stories begin like that. The long train was made up of cattle trucks, not always with bedframes; sometimes people had to sit or lie on the floor. All ages and sexes were crammed together. And then the journey was long, very long with no place of the destination given at the start.

Suggest

To suggest a room, archives comment. You can select the room in the right-hand column that corresponds to your choice.You can also contact us by e-mail to: contact<at>gulagmemories<dot>eu

Daily life

The day was filled up with work on the kolkhoz and various household tasks, made more tiring because this was a world with a minimum of artefacts. Most of the object were made by the peasants from local materials: wood, linen, hemp, leather, and plant roots used as soap or onion skin to dye cloth. The deportees recount their exile through a few key objects that represented their poverty or, in some cases, a source of hope: the pigs that were reared some years after the war revealed an important improvement in the living conditions of those who owned them.

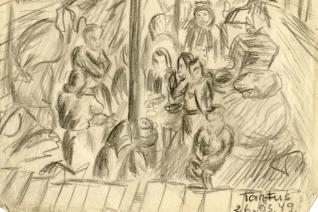

A world of women?

Many witnesses remember arriving in huts in Siberia where there were only women and their children. This world of women recurs in their recollections, and often the only male present was the commandant who came once a month to check on the various families in restricted residence in a village. The men, the fathers, were in camps, from which some would return and others didn’t. Some deportation orders specifically included “instructions for separating the deportee’s family from its head”.

Hunger

Hunger, not having enough to eat, being constantly hungry, being obsessed by finding something to eat, suffering scurvy and night blindness for lack of vitamins; all these are physical and psychological conditions that recur in the stories of our witnesses, particularly those who were children when they were deported.

Taiga

An essential part of Siberia, the taiga was an inevitable feature of life for the resettlers. The forest was an ambiguous place: associated with the pain of the work of the resettlers allocated to logging kolkhoz, with freezing cold and fear, it also offered essential supplements to their rations. From 1941 to 1946 in particular, when war made the resettlers’ living conditions appalling, the berries, nettles and other plants were eaten for food or as makeshift medicine. The children, who usually had the task of picking them, made a direct contribution to family survival.

The steppe

Nombre de déplacés découvrent les steppes, ces grandes plaines semi-arides, à leur arrivée en relégation dans le Sud de la Sibérie ou le Nord du Kazakhstan. On estime qu’à la mort de Staline en 1953, plus de 600 000 exilés vivaient dans les régions de steppe ouverte du Kazakhstan, où étaient notamment établis d’imposants complexes pénitentiaires comme le Karlag (à Karaganda) ou le Steplag (littéralement « Camp de la steppe »).

Work in deportation

Work was the centre of life in deportation. It was the whole of life in the camps. It was essential both for survival and for integration into the world where the deportees would have to live.Work in the villages of special resettlers was different from that in the camps. It was usually rural work. In the camps, the prisoners were used mainly to build towns, railways, and factories and to open up and work coal and mineral mines. The distinction between special resettlers and prisoners was not a hard and fast one. For example, there were agricultural camps.

The others

For most witnesses, resettlement, life in the distant camps and special settlements in Siberia and Central Asia were their first experience of living with people of different national and social origins, speaking other languages, having different beliefs and customs, and having in some cases fought on opposite sides.

Languages

Les langues, leur apprentissage, leur pratique, voire leur perte, sont des marqueurs importants des expériences de déportation. Elles sont souvent un moment de rencontre avec de nouvelles langues, qu’il s’agisse du russe que les enfants apprennent à l’école et emploient entre eux, ou des langues d’autres populations déportées, qui font parfois l’objet d’un apprentissage mutuel entre déplacés ou prisonniers. Mais la déportation pose aussi l’enjeu de la sauvegarde (voire de l’apprentissage pour les tout jeunes enfants) de la - ou des - langues natales

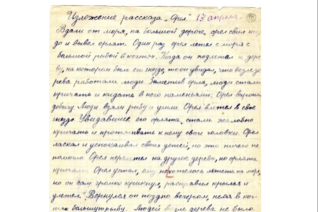

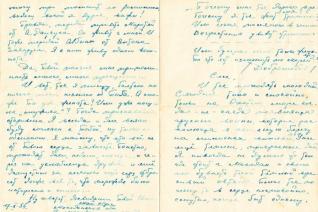

Letters

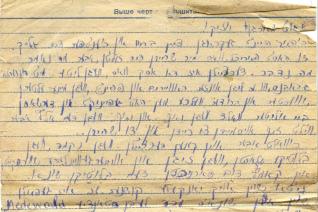

Deportation and exile did not sever the bonds to friends and family who had escaped forced departure. Letters went to and from Lithuania to Siberia, between family members and a few friends, letters that were closely monitored by the postal controllers, who focused on those from the Western republics to the ‘distant territories’ to which people had been deported.

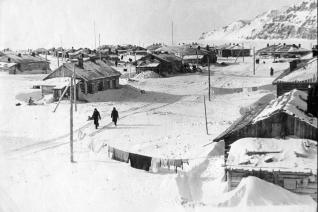

Places of resettlement

Within a few hours, the deportees left the farmhouse or the town flat where they lived and were loaded onto cattle wagons. They stayed there for a long, uncomfortable journey to places of whose location and nature they knew nothing.When they arrived, there was often nothing planned for permanent settlement. They were crowded into huts, the buildings typical of the Soviet prison world and also of workers’ accommodation. Some of them lived in houses abandoned by their former occupants, who had themselves been purged or had moved elsewhere.

Status

At the end of the train journey, after days or even weeks, their new life was not necessarily in a forced labour camp. This was only the case for those who had been given a court sentence, however summary. Most of the European deportees were arrested under collective deportation decrees issued by the administrative and police authorities.

The territories of resettlement

The geography of resettlement destinations is similar to that of the camps. The camps were scattered across the Soviet Union, with more in inhospitable or mining areas, or railway and factory construction sites. The special resettlers were sent mostly to farming or logging areas. There were no special resettlements west of a line from Leningrad to Moscow, although there were many camps there.

Childhood in the Gulag

After the Red Army’s advance into Eastern Poland and the Baltic states, waves of deportation begin in 1940. Families are sent with their children to remote villages in Siberia and Central Asia; children are born there. Although some go to school, most have to work. Some spend time in orphanages.

The camp prisoners resist

After 1944, there were many prisoners in the camps who had been sentenced to long terms of hard labour for taking part in civil and armed resistance against the Sovietisation of Western Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The arrival in the camps of these political prisoners with recent experience of war and the underground struggle against Soviet rule played a major role in increasing all sorts of infringements of rules and resistance: group escapes, hunger strikes, work strikes and uprisings.

Death of Stalin

On 5 March 1953, Stalin dies at the age of 74.Millions of Soviet citizens and Communists throughout the world are in mourning.For prisoners in the Gulag camps there is at last some hope of liberation. All of them recall that memorable day when the news of his death is announced at morning appel.

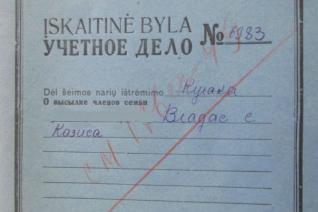

Liberation of displaced persons from Lithuania

The liberation of special displaced persons from the Western territories occurred slowly after Stalin’s death. This slowness reflects the authorities’ considerable hesitation and reluctance: deep distrust of groups who might resume insurgent activities; fear of tensions on their return home; reluctance from the regions they had been deported to, which would lose cheap but valuable labour.In Lithuania, the liberation occurred in two ways:

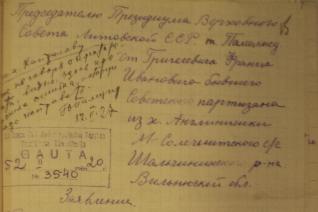

Appeals

The exiles did not just accept their fate, but found various ways to evade it. Even before Stalin died, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and other deportees wrote letters attacking the errors and injustices they had suffered. They sent them to senior officials in the Soviet state, the authorities in their own republics, the Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, First Party Secretary, Chief Prosecutor of the USSR, Commissioner or Minister of Internal Affairs, etc.

Surviving by deportation

Many Polish and Baltic families of Jewish origin were deported in 1940 and 1941 because of their social background, political and ideological militancy or as refugees who had fled eastwards from the western parts of Poland occupied by the Germans. Caught in what was now western Soviet Ukraine, they were offered citizenship. Those who refused were deported to Siberia or the Great North.

Becoming Soviet?

After the repeated violence they suffered while they were being deported, many special resettlers, once they had arrived in Siberia or Central Asia, discovered a world that was harsh but offered some chances of integrating. The living conditions of the local people were surprisingly similar to their own. They shared the same experience of manual labour on the kolkhoz collective farms and in the forestry industry.

Life after the Gulag

A minority began to return from the camps and resettlement after the war, but the great wave of amnesties and liberations began after Stalin’s death and continued until the early 1960s.Prisoners and resettlers returned after a long journey to native lands they did not recognise, with a changed political regime and sometimes changed borders (Baltic countries, Poland and western Ukraine), to families often decimated by war and purges, and subject, like the entire population, to systematic checks of their biographical background.

Memoir literature

Deportees from outside the USSR’s 1939 borders have left behind a considerable literature of memory, not only in their own languages but also in Western European languages. When they were released, some went to France, the United Kingdom or the United States and wrote their memoirs in English or French. There were two main waves of writing: immediately after the Second World War and then after the late 1980s, particularly between 1990 and 2000.